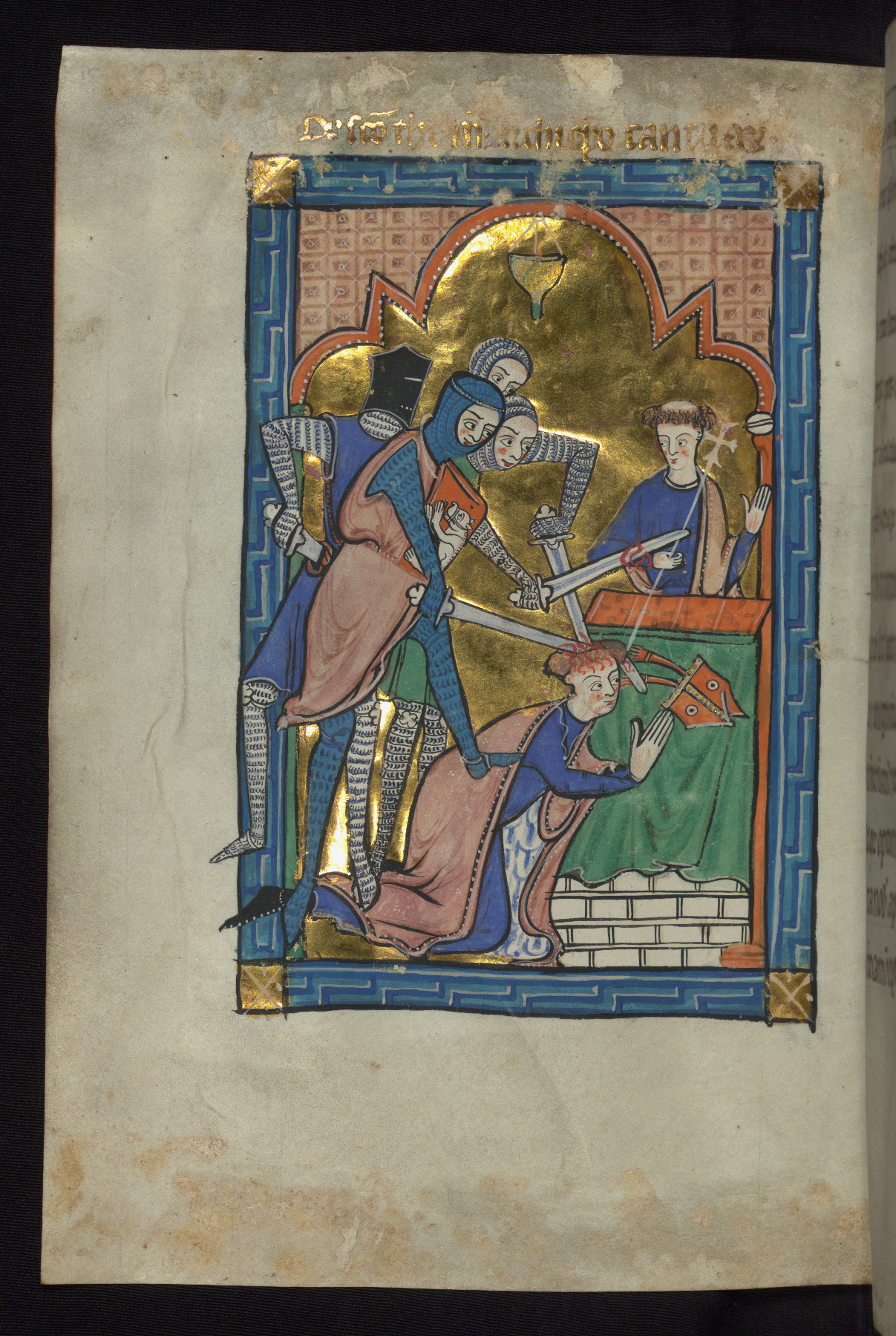

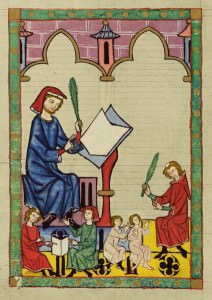

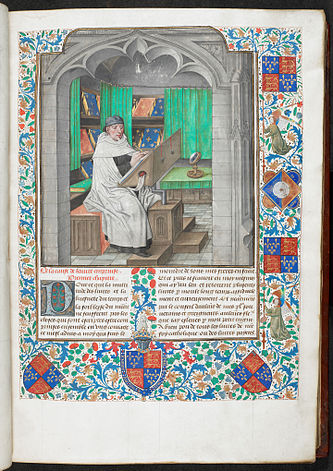

The fancy clothes and posh accents of the spokesman and the courtly ladies put a little polish on the fact that we're watching an ad about shitting and farting. And the clothes themselves are a mix of ancien regime wigs and panniers for the ladies and mock-Tudor doublet and slashed sleeves for the spokesman, signifying a generalized "pre-modern" period ("Humans have been pooping for over a hundred years"). Even the child in the Unicorn Gold (tm) ad reflects the tendency in European portraiture in the 17th-19th centuries to depict children clothed like small adults. During the late Gothic period, the unicorn often signified rarity, beauty, and purity. The use of "real freaking gold" recalls the importance of potable gold as a panacea in medieval and early modern medicine (for those who could afford it), and the admonition to use Unicorn Gold (tm) "when you pay your taxes to King John" is a neat pun as well as an allusion to the plot of virtually every Robin Hood storyline in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Using medievalism to advertise products related to poop aligns with existing ideas about the grossness of "the Middle Ages." Yet, in a neat inversion of this existing association, the past portrayed in these ads is also more desirable than the present. Hemorrhoids are brought on by the design flaws in modern plumbing; the toilet does not accommodate the human body. And it can be said of the people of Ye Olden Days (at least for the ones who use Unicorn Gold (tm)) that their shit don't stink. Medieval is the new modern.