|

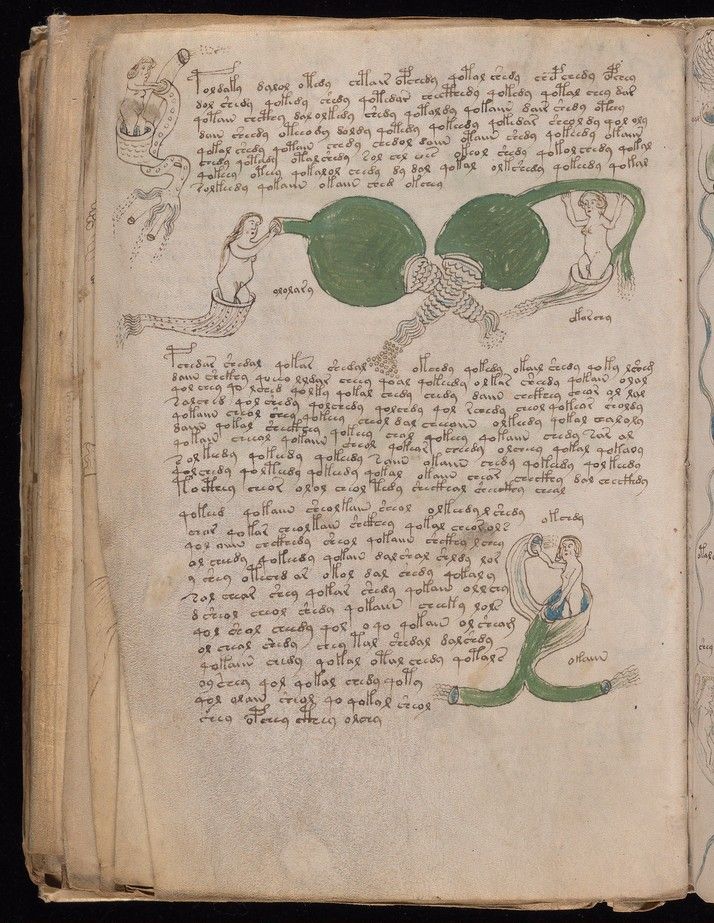

| Yale University Library, Beinecke MS 408, fol. 83v. |

The mysterious Beinecke MS 408, also known as the Voynich MS (after the rare book dealer who acquired it from the Jesuit College in Rome in 1912) has been back in the headlines recently. This strange book, written on fine parchment, has been an enduring and alluring mystery for codebreakers and treasure-seekers. Written in an elegant cursive hand, the alphabet and language are unintelligible. The writing accompanies a number of color illustrations of plants and celestial charts that are not found in nature, and numerous drawings of naked women in baths, all drawn with care and artistry.

A few months ago, one man claimed to have solved the riddle of the Voynich's mystery alphabet, only to be soundly debunked days later. The Voynich has a history of attracting fraudulent claims; an academic named William Newbold claimed in 1921 to have broken the cipher, only to be revealed to have made it all up a few years later.

Other cryptographers have worked on the Voynich since the 1920s, including some of the most important figures in American cryptography in the twentieth century. William and Elizabeth Friedman, based at Arlington Hall, worked on the Voynich from the 1920s until the 1960s, and eventually concluded that the script was of an attempt to create a universal language. More recently, researchers in Brazil and Canada have claimed to find clues to the text's meaning, using big data methods to uncover Hebrew letters as the basis for the mystery language of the text. But the words still seem like gibberish.

The text may also be a hoax. The earliest provenance of the book remains unknown, but it enters the historical record in the early seventeenth century, as the property of Jacob de Tepenec, pharmacist to the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II. The material of the book, its parchment and binding materials, date to right around 1430. Books of secrets were expensive, sought-after items by princes, physicians, and wealthy adepts; Rudolf II ultimately paid 600 ducats for the book. Hoaxes and forged texts abounded in the medieval period, from forged charters like the Donation of Constantine to historical texts that have elaborate frame stories of lost books in ancient and forgotten languages.

Why not think of it as a hoax, but as a puzzle? Is it the allure of the idea that a hidden key will unlock this alphabet and its secrets, a la the Rosetta Stone? That is a potent story--with that one discovery, a past civilization became legible to the present in its own words, the distance between them collapsed into a tablet. In the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, many who became interested in hermeticism, alchemy, and other now-esoteric subjects believed that recreating or rediscovering pre-Adamic language would unlock the secrets of nature, expose hidden sympathies between the microcosm and the macrocosm, and allow one to know God more fully. Or perhaps the impulse to decipher the Voynich MS arises fro the desire to impose meaning on something nonsensical? That can have its own hypnotic effect, too: