|

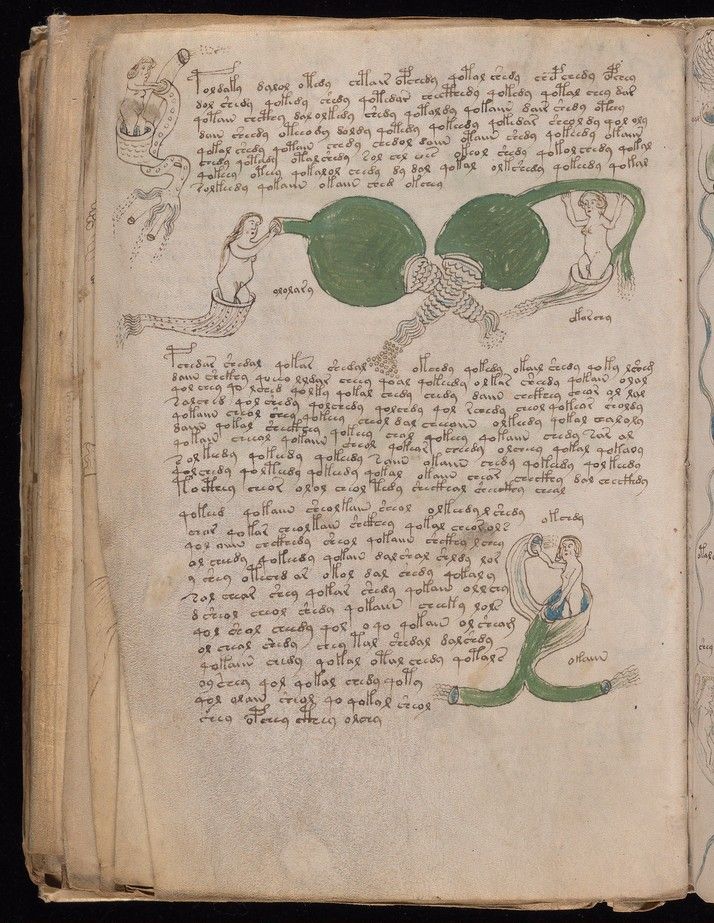

كتاب سرّ الاسرار

Kitab sirr al-asrar, ca. 1200, Mosul. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania,

LJS 459, fol. 114v.

|

1) Sitting in a class and focusing for 80 minutes is difficult and exhausting. If you teach, you need to be aware of this. Sitting in class is far more taxing than teaching a class, even though teaching is often an intense activity. Thank god my language teachers are always getting us to move around and talk to each other.

2) Traditional-age college students are awesome. I love getting to interact with them as my fellow classmates, rather than as their professor. The anxiety and stress they feel about "will it/will I turn out okay?" is real. And it turns out that being in class with a bunch of whip-smart 18-year-olds keeps me on my toes. Which leads me to...

3) Learning something completely new is unbelievably invigorating. Yes, it's tiring, and sometimes frustrating and a grind, but it is also the best ever. It's exciting and exhilarating to stretch your brain in new ways.

4) Arabic is an incredibly fun language to study, especially if you like aural or visual patterns, and incredibly rewarding grammatical structure. Persian, next?

What will you be learning?